Shortly after the 1981 riots in Brixton, South London, founders of the legendary London based punk rock venue the Roxy Club, Andrew Czezowski and Susan Carrington opened their new club, The Fridge, located in a small club above the Iceland frozen food store in Brixton Road, “with a radical décor that included beat-up fridges, a pyramid of broken TVs showing John Maybury videos and (fake) dead cats hanging from its ceiling.”[1] The installation of 25 old television sets stacked up and chained together around the dance floor, was created by London-based French artist Bruno de Florence. As well as creating the ‘The Video Lounge’, twice a week de Florence ran the space, screening his own work and that of fellow video artists. With potentially several sources of video being sent to and split across the 25 monitors, by 1984 de Florence was pioneering the creation of what came to be known as Scratch Video, in ’the first regular venue for video in a nightclub’[2].

At its best for about seven months, various makers would turn up with their latest work and sit around while a sizeable crowd – who’d probably never even heard of independent videos – watched their handiwork on banks of old DER monitors, some upside down, some even, artistically of course (what else?), on the blink. (Barber, 1990, p.114)

De Florence’s evenings drew together an eclectic mix of young video makers. Their influences, practices and engagement with technologies divergent from the structuralist and formalist concerns of much video art and experimental film practice dominant in the UK during the previous fifteen years, marking ‘a “new” artistic and epistemological space, sidestepping the creative embargo set up by structural film’ (Birtwistle, 2010, p.271). Screening work myself at the Fridge at this time, having encountered flyers for de Florence’s nights whilst looking for distribution outlets for View From Hear and becoming a contributor to the nascent Scratch canon.

The ready availability of VHS domestic video recorders introduced into Britain in 1978 were becoming more affordable, technically sophisticated and widespread by the early 1980s (Armes, 1988, p.84), and facilitated the easy and cheap recording of off-air broadcast television footage. Re-editing and recontextualising this footage was the modus operandi of Scratch, sometimes using image processors to affect the colour, texture, size, shape and montage; often, as Rees notes ‘to create parody’, with ‘Reagan, Thatcher and the “military industrial complex” as main targets’. Scratch video was ‘politically astute and sharply cut (often to rock soundtracks)’ (Rees, 1999, p.96). The radical implications of these new technologies recognized by Birtwistle,

“For the first time ever, the sounds and images of broadcast television became permanently available to almost anyone who wanted to record them. This not only provided scratch artists with the material content of their work, but also signaled a change in the relationship between the producers and consumers of television. In short, the VCR prompted and supported a culture of audiovisual appropriation that found its most immediate manifestation in scratch (Birtwistle, 2010, p.244-245).”

Scratch video artist George Barber credits journalist Pat Sweeney with coining the term Scratch Video in 1984 (Barber, 1990, p.116), ‘comparing it to New York’s Hip Hop scene’, which by 1982 was well established and making in roads into UK club and music culture[3]. Significantly, new edit suite hardware that could facilitate video editing accuracy to within 1/5 of a second or more was becoming cheaper, easier to use and more accessible, in particular via community video workshops and art colleges. ‘Editing was central to Scratch…The first wave of ‘decent’ technology did indeed help delineate an aesthetic and make achievable the first truly edit based video form’ (Barber, 1990, p.115).

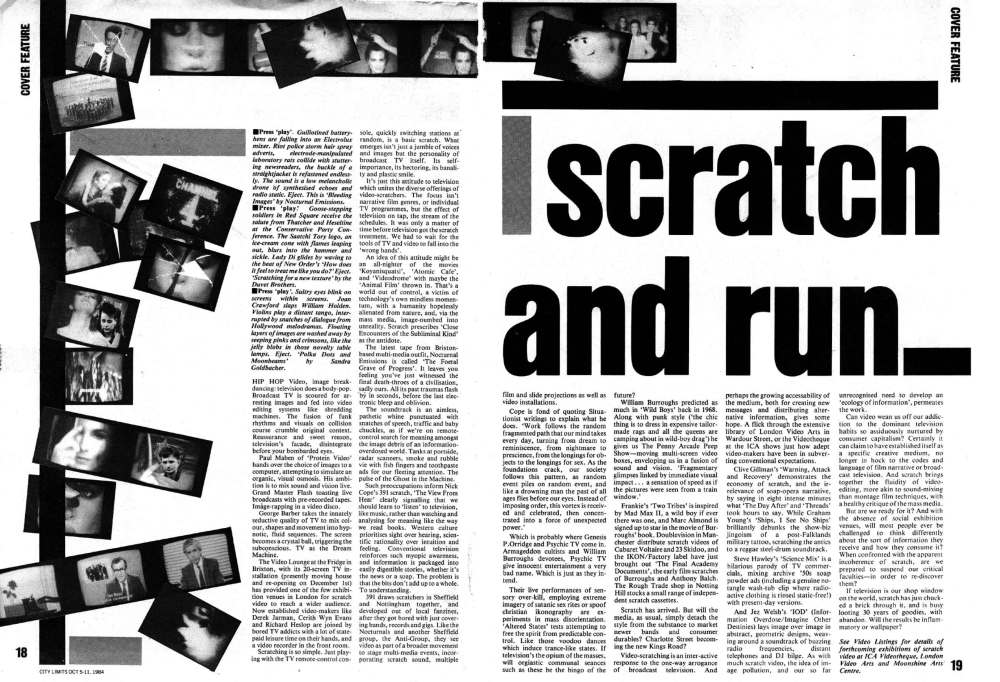

Writer and journalist, Andy Lipman, would publicise Scratch Video for the first time in his cover article ‘Scratch and Run’ for London listings magazine City Limits in October 1984, having made it his business as editor of the magazine’s weekly video column to get to know all the artists involved in screening work at The Fridge.

“Hip-hop video, image break-dancing: television does a body pop. Broadcast TV is scoured for arresting images and fed into video editing systems like shredding machines. The fusion of funk rhythms and visuals on collision course crumble original context. Reassurance and sweet reason, television’s facade disintegrate before your bombarded eyes … Video scratching is an interactive response to the one-way arrogance of broadcast television.

…If television is our shop window on the world, scratch has just chucked a brick through it and is busy looting 30 years of goodies, with abandon (Lipman, 1984, pp.18-19).”

Lipman would go on to list a diverse collection of individuals and groups working with video, drawing reference to underlying themes of political oppositional practices, strategies of questioning and subverting broadcast television, and an alliance of alternative music and ‘industrial music’ practices and practitioners, video artists, arts organisations and pop cultural remixing. Specifically naming work by Nocturnal Emissions, Duvet Brothers, Kim Flitcroft and Sandra Goldbacher, Paul Maben/Protein Video, George Barber, Derek Jarman, Cerith Wynn Evans, Richard Heslop, The Anti Group, Psychic TV/Genesis P-Orridge, Doublevision and IKON, Clive Gillman, Graham Young, Steve Hawley, Jez Welsh and Nick Cope/391.

A playlist of selected Scratch work is here

and Scratch works by Nick Cope here

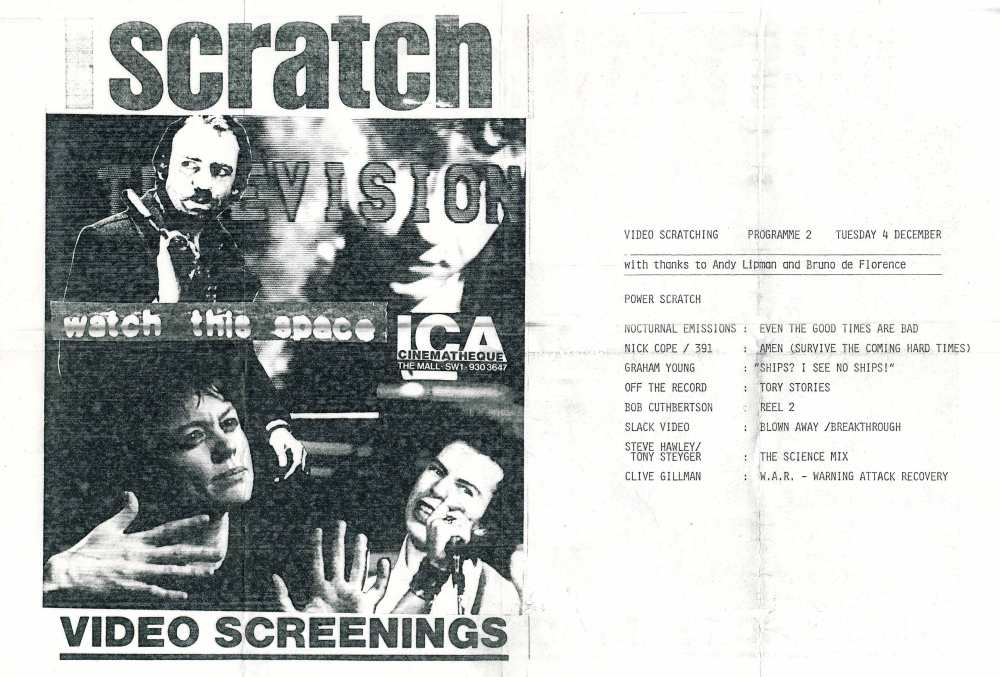

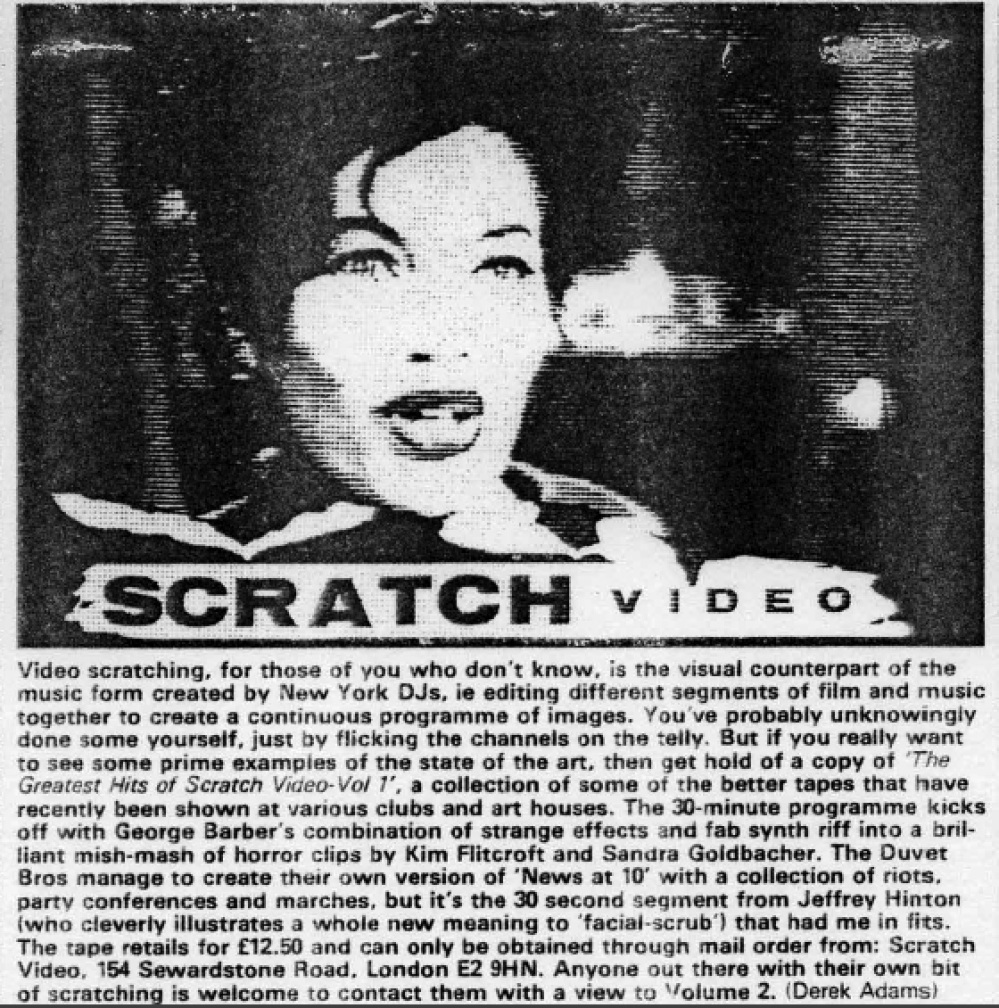

Whilst the earliest screenings of Scratch were outside of any gallery contexts, Lipman and De Florence would curate the first gallery screening of this work, Scratch Television: Watch This Space, at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, in December1984. Soon followed by the recently formed Arts Council funded Film and Video Umbrella’s second touring programme – Subverting Television curated by Mark Wilcox and Michael O’Pray, and a further programme of Scratch works curated by O’Pray and Tina Keane in the 1985 show at the Tate Gallery, London, ‘The New Pluralism: British Film and Video 1980-85’. With George Barber compiling for independent distribution a two-volume collection The Greatest Hits of Scratch Video on VHS, a canon of Scratch video works was emerging [see: Appendix 3, 16 & 17]. The Duvet Brothers would tour their Live Multiscreen Scratch multi-monitor show nationally and internationally for three years between 1984 and 1987[4], but Scratch was very much a short lived phenomenon, with most of the key artists moving on to other work and projects, and no further significant screenings following the Film and Video Umbrella tour of 1985, until 2008.

Scratch Television, ICA screening programme, 1984; featuring Nick Cope/391: Amen (Survive the Coming Hard Times).

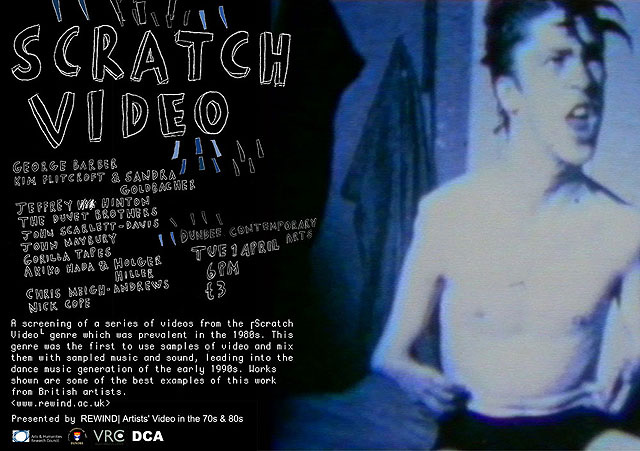

In the programme notes for the retrospective ‘Scratch Video’ screening at Dundee Contemporary Arts in April 2008, the curators wrote of Scratch video being ‘generally forgotten about in contemporary culture’. Noting the contemporary relevance of themes in the Scratch work selected, and the pioneering use of sampled music and sound in conjunction with video sampling and mixing, which would lead into the ‘dance music generation of the early 1990s’[5].

Other than Andy Lipman and Michael O’Pray’s championing of Scratch, initial critical reaction appearing in the specialist magazines Independent Video and Undercut was partisan, harsh and damning. Tending to concentrate on the swift recuperation of Scratch techniques by broadcasters and a dismissal of Scratch’s engagement with the new technologies of post-production as empty techno wizardry. Lipman responded that this criticism,

“…misses the point about the practice of scratch, regardless of the end product, which anticipates the inter-active era of electronic networks, where the combination of video and computer promises to allow the exchange and re-processing of information, into new visions to suit individual taste. Unlike the one-way system of current broadcast media, there could be a network resembling the telephone system, where calls, or programmes, or computer software could both be made and received by each individual. Such developments raise fundamental questions about the status of the ‘artist’ and art objects. Scratch takes the broadcast media as its paintbox, the video recorder as its palette, and the TV screen as its canvas (Lipman, 1985a, p.10).”

Anticipating Internet developments to come and the explosion in creative possibilities forged by emergent, convergent, digital media as well as sampling and remix technologies and practices. Lipman highlighted the fundamental issues surrounding the ‘pirated’ use of imagery and ‘the inherent challenge to copyright law’ that Scratch raised, and which Scratch artist Jon Dovey would later give a personal account of in ‘Copyright as Censorship’ (Dovey, 1986), anticipating again important debates that would develop around sampling technologies/plunderphonics/online mash-up culture and file sharing[6].

Subsequently, over the next twenty-five years a small but steadily increasing number of texts have addressed the impact of Scratch amidst an ongoing re-evaluation of its impact and importance with the benefit of historical distance and growing critical context.

Some commentators have found the close relationship between the source material Scratch artists were drawing on, and a concurrent critique of media through that same material problematic (Elwes, 2005, p.115) and most note that broadcast television was quick to appropriate and recuperate the visual styles of Scratch, albeit loosened of the political bite and agitational attack. Whilst this appropriation is often written of as a flaw and weakness of Scratch, it also evidences the powerful impact that such a small and short-lived video art genre was to have on the look and style of mainstream media.

Rees (1999, pp.106-7) makes evident the connections between this generation of filmmakers and their roots in the ‘punk-era revision of the underground’ through the encounters of Ken Russell, Kenneth Anger, Derek Jarman, Genesis P-Orridge of Throbbing Gristle and William Burroughs. Resulting in a fusing of Jarman and P-Orridge ‘tendencies’ with younger filmmakers ‘drawn to their world of free play, extremist imagery and a hallucinatory “dream-machine” cinema’; a “new punk underground”, who lead a ‘rebellion against the structural avant-garde which preceded it as a distinct aesthetic direction’ (ibid, p.86). Mapping connections too between the scratch artists, low budget promo practices which explored new forms of hybrid editing ‘moving from film to video and back again’, and ‘the largely 8mm film-makers in the “New Romantics” camp’.

The location for the initial screenings of Scratch work is significant and points to an overseen aspect of Scratch, that many of the works produced are visual music compositions, designed to be screened in nightclub venues, as much as on a TV monitor, and to be listened to as much as seen. Philip Hayward picks up on this aspect,

“Although the majority of scratch video pieces produced during 1984/85 were not specifically made as record promos, the majority were set to contemporary music, most often the style of American dance music known as Hip Hop, and were usually three to four minutes duration (standard music video length). Drawing on the ‘impact aesthetics’ of the music video form, these video collage pieces were initially screened at fashionable nightclub venues before a number of them were made commercially available on video compilation cassettes. From the beginning, individual scratch tracks and the two highly influential compilations… were packaged and promoted akin to music products, or music video compilations, rather than as either video art or independent film releases (Hayward, 1990a, p.134-5).”

George Barber notes that ‘Nightclubs… helped ground an aesthetic for both the New Romantics and Scratch – one of “visual pleasure”… Scratch looked its best in nightclubs rather than screenings, clubs were its spiritual home’ (Barber, 1990, p.114)[7]. Elaborating on the edit suite technology developments that facilitated Scratch aesthetics, Barber makes mention not only of cutting and mixing images using a music track as a guide (ibid, p.115), but also of the importance of the invention of the music computer/sampler at this time in parallel with the cross fertilization of ideas, quoting across cultures and cultural forms[8].

City Limits Magazine feature on George Barber’s ‘Greatest Hits of Scratch Video’ VHS cassette release.

In one of the most recent reappraisals of Scratch, Andy Birtwistle recognises a profound and radical exemplar in innovative sound and image compositional practice, and an equally radical challenge to its critics,

…While scratch represents a highly productive encounter between music and the audiovisual, that in some senses realizes earlier radical visions of both an art of organized sound and an art of visual music, the musical dimensions of scratch proved problematic for those trying to situate its audiovisuality within existing political frames of reference. Central to its politically problematic status was the issue of how sensation and affect might be situated within radical modes of audiovisual practice. Scratch is intimately linked with music, which not only forms one of its key constituent elements, but also provides the primary formal model for its mode of articulation (Birtwistle, 2010, p.241).

Birtwistle places Scratch in new and emerging contexts of affective cinema and audiovisuality, what he defines as cinesonics. Maintaining that Scratch was pioneering forms of audiovisual practice ahead of critical discourse,

The critical difficulties faced by avant-garde film and video in its attempt to territorialize scratch mark the point at which established conceptual models reveal their own deficiencies and biases, in terms of the way in which they conceptualise the cinesonic, and the cinesonic experience. What we see and hear in the case of scratch is the point at which the dominant modernist formulations of sound-image relations are challenged by other radical conceptual models of the cinesonic (ibid, p.248).

What we see in this moment is the emergence of an affective or sensory turn, arising before the vocabulary was in place to deal with it. For the critics of the time, scratch simply did not make sense; they were unable to situate the affective and sensational dimensions of the form’s audiovisuality within existing critical and theoretical frameworks. All the critics of scratch could see were insufficiencies, and it has taken more than two decades for this moment to be affirmed as a radical departure from the critical and creative agenda set in motion by the linguistic turn of structuralism (ibid, p.272).

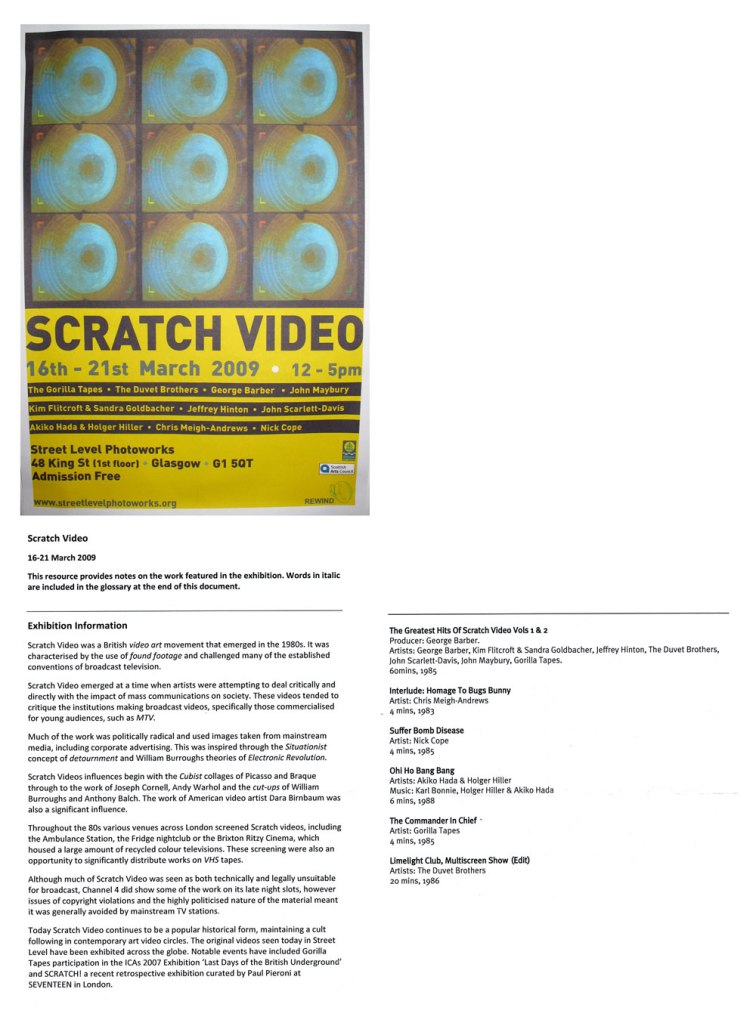

Rees in 2007 would acknowledge that the ‘short-lived but very effective’ movement, ‘was also the most explicitly political video art in ten years’; and Sean Cubitt (2009) in a webcast at the 2010 retrospective installation Scratch Video, at Glasgow’s Street Level Gallery, in March, 2009 would declare that ‘video and video art became for that brief period the one true British Avant-Garde of the twentieth century.’[9]

Scratch Video installation, Glasgow, 2009.

Suffer Bomb Disease included in the programme of works screened as a week long installation, Streetlevel Photoworks Gallery, Glasgow, March 2009.

[1] http://www.fridge.co.uk/ [accessed April, 2010]. See also; http://www.deflorence.com/?p=283; De Florence would later go on in 1987 to set up and run London’s first and only Pirate TV Station Network 21.

[3] See: Toop,1991; p.134, p.184.

[6] See: Mason (2008); and Gold, Eno, Oswald, Cutler and Eshun in Section 3 – ‘Music in the Age of Electronic Reproduction’ in Cox, C. and Warner, D. (2007).

[7] An important aspect picked up by Birtwistle too;

Its true home was in the club environment rather than the gallery or the cinema. The club experience itself can be thought of as a form of sensory blending, a fusion of sound and image and bodily movement. And in some ways it is this form of transsensoriality to which scratch video aspires in its synaesthetic articulation of sound and image; scratch is a mode of articulation that places emphasis on blending and folding rather than isolation and specificity. Little wonder, then, that scratch got the reception it did in the 1980s, a period in which British avant-garde film and video practice was dominated by a visually oriented critical culture founded on modernist notions of specificity (Birtwistle, 2010, p.265).

[8] In forms such as Pop, Fashion, Sculpture, Architecture and Cultural Studies, themes and emphases cross fertilized and video embraced these developments. Again a convergence of technology appeared perfect for this task… In practice it became possible to musically repeat stolen voices and small phrases of dialogue, quoting in an exciting and rhythmical way. Sound bytes or noises could be stored on disk and a music track. Thus, after the sound was perfected, the pictures could be synched in place (Barber, 1990, p.116).

Barber is clear about a certain way of working that was intrinsic to the Scratch aesthetic, significantly citing the musical term ‘jamming’,

I… would cite Scratch as a prime example of where available technology was made the most of, where people just got on the machines and ‘did things’. They jammed, winged it and made it up as they went along. It would take a philistine to say it was ‘just effects’ pure and simple. One only has to look at broadcast television to see its legacy… the grammar of editing and visual language have irredeemably changed, copying over the excitement of the Scratch scene (ibid, p.123).